Building an SQL database with 10 Rust beginners

This summer I was overseeing a three week university programming practical focussed on the topic of databases. My group’s task was “simple”: build your own SQL database. Considering the complexity of database systems (with SQL parser, network interface and storage engines), one might say that this was already an insane idea. But wait, there’s more! We used the language Rust for every part of the software although none of my team had even heard of the language before. This post describes what happened and what my students think of Rust after working with it for three weeks.

Starting with Rust

Sadly, pretty often programming practicals at my university are chaotic in the beginning: the students show up unprepared on the first day; their programming experience varies widely and is often limited to Java. Therefore we usually start with a quick introduction to git, which is used extensively throughout the practical. My group obviously needed an introduction to Rust as well.

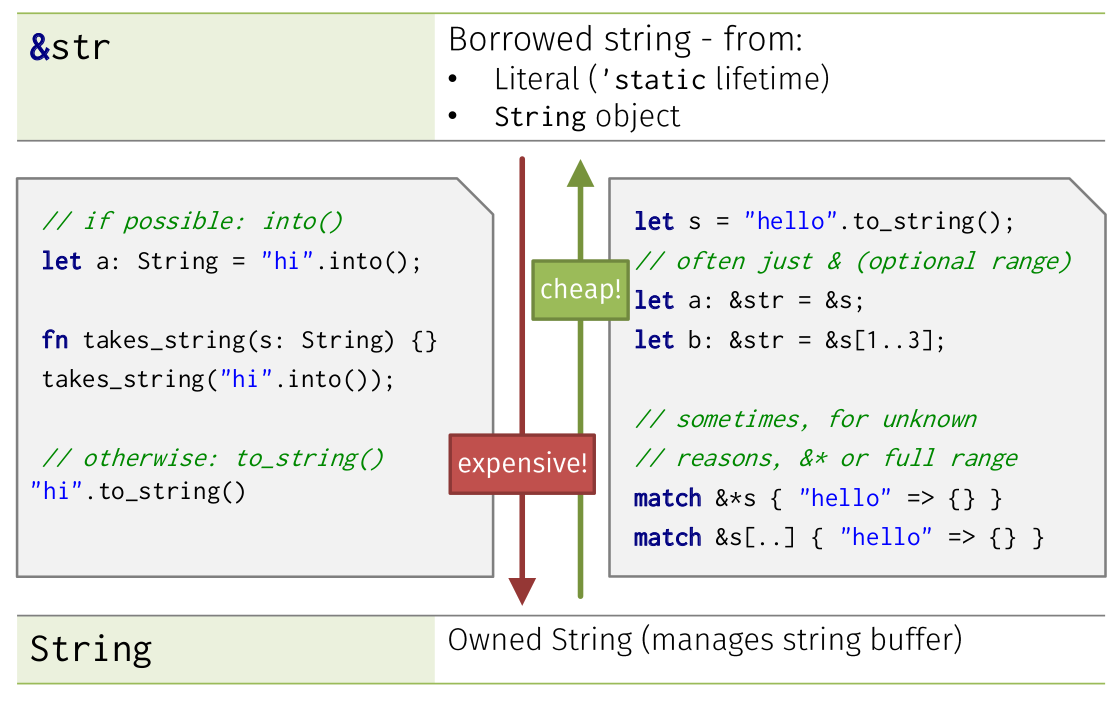

My Rust introduction on the first day took about 90 minutes and covered only what’s really necessary: basic syntax, the surface of ownership and borrowing, struct and enum types as well as a hint to the standard library. That’s hardly enough to write professional Rust software but enough to take in on the first day. After having practised the language with some exercises in the afternoon I explained a few more concepts on the second day, including traits, closures, generics and… how to deal with those wicked strings! Of course there wasn’t enough time for a detailed explanation.

A slide of my Rust introduction

A slide of my Rust introduction

As it turns out, Rust strings really confuse people – especially if those people only know languages, like Java, with one (main) string type. And granted: Rust strings are complicated, even if you’re familiar with system programming languages. Ask three Rust developers about the best way to convert a &str into a String: you will probably get three different answers. As you can see in the picture above, I told my students to use into() where possible and to_string() everywhere else. Then there is String::from_str(), which is deprecated now in favour of String::from, which should be equivalent to into(). There is also to_owned(), which is probably faster than to_string() but only works for &str. There are at least three more ways to do this seemingly simple task – String to &str is not trivial either; I’m not surprised that people get confused by Rust strings.

Working on the database system

After only 1.5 days of teaching Rust, my group, separated in three subgroups, finally started with the project. The subgroups’ tasks were:

storage: writing table meta data into files, defining a storage engine interface (Trait)parse: lexing and parsing SQL strings into an ASTnet: defining and implementing a network protocol to communicate with clients

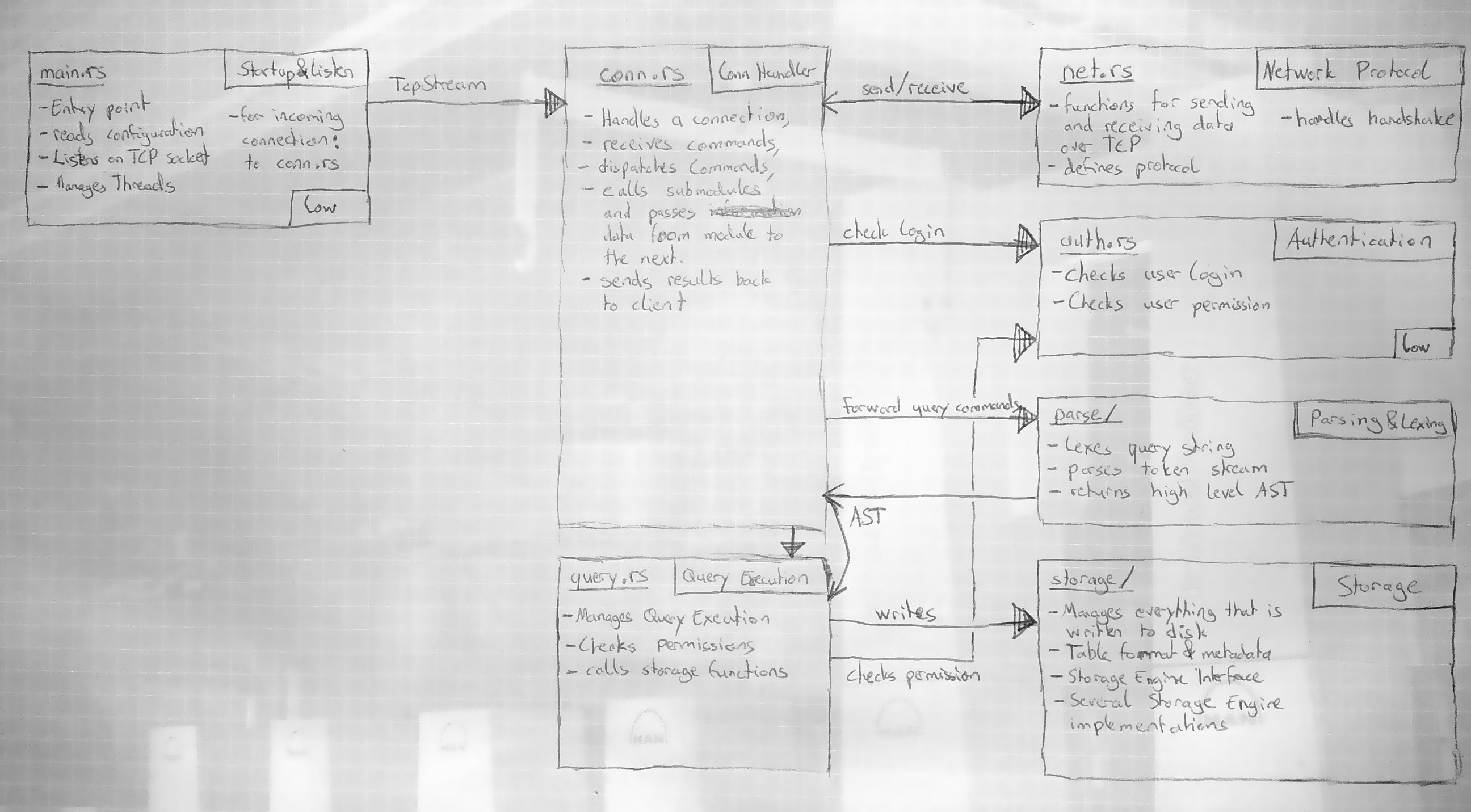

An early sketch showing the structure of our database server.

An early sketch showing the structure of our database server.

I already provided a very basic project structure to ease the beginning. Two teams, net and parse, were surprisingly quick: a basic parser and a working command line client communicating with the server were ready at the end of the first week. After the parser had been finished and was able to parse the subset of SQL we wanted to use, the group split up. Two people were working on the query execution module, which takes the produced AST and calls the appropriate methods from the storage module to execute the query. The other two worked on some small features, like command line arguments, first and on a web client, similar to phpMyAdmin, later.

The net group created a Ruby library to communicate with our server, too. They also updated another project to stable Rust while adding two command line games as Eastereggs to their Rust client. The storage group was not that successful, but they had a basic implementation that could create, read and modify tables with the four basic SQL operations. Someone from the former parse group even implemented a working B+ tree but didn’t had enough time to integrate it into the main project.

The project’s source code can be seen here on GitHub. Please keep in mind that pretty much all code was written by Rust learners, which most certainly means that most code is not optimal, not idiomatic and completely chaotic. There is also a German documentation, which can be found here.

Sadly, we did not measure the performance of our database system. My group simply hadn’t had enough time for that and the results would have been pretty sad anyway, I guess. Our only working storage engine was a simple heap file that has O(n) runtime for most operations and the Rust code was not optimized in any way. The parse and net module should be reasonably fast, though.

The project was pretty nice for most parts. Our professor was surprised how much my group achieved and I think it’s a pretty good accomplishment for a bunch of Rust beginners.

Impression of Rust

I asked my students to fill out a short anonymous evaluation about Rust afterwards and I got nine answers. Most of them thought that my introduction to Rust had been pretty helpful and there was only one real complaint: the concept of lifetimes and borrowing should have been explained in more detail – and I agree. Given the very limited time, I decided not to talk about that in-depth. However, only a few people had problems with it; many never had to handle any complex lifetime situations.

The language itself got mostly good responses. Seven students stated that Rust is a (very) modern language with high level concepts, which allow writing down algorithms in a very compact form. Six said that coding in Rust was (far) more fun than coding in other languages familiar to them. “It was fun to work with Option and Result” and “More compact and clear than Java” were two comments about that.

The majority of my students were satisfied with the compiler error messages; just one answered that they had not really helped him. I also asked how much information about Rust can be found online. Since Rust is a pretty young language it surprised me that the results weren’t too bad: only four responded that there is not enough information, while three said it’s “ok” and the last two stated that the situation is “good”. The Rust book and standard library documentation were praised by one comment – especially for linking interesting papers. The group that created the Ruby library also said that the Rust documentation is better than Ruby’s.

Of course there were negative answers, too. “Missing” features like function overloading and the ++ operator were criticised, lifetimes and the need to prefix every field access with self. were called annoying.

Overall the response is pretty great in my opinion. I was particularly delighted by two things I’ve overheard during the practical: One student was super amazed that enum types can have methods, too, and in the end someone noticed that he hadn’t used mut very often while programming. The last thing is pretty interesting, because the common reaction to immutable by default is something like “which use does a variable have, if I can’t modify it?”. I’m really happy that Rust tends to be pretty functional sometimes.

I wanted to share this information about the experiment and the evaluation results with the Rust community to further improve the Rust ecosystem. Hopefully next year’s programming practical about computer graphics will use Rust as well…